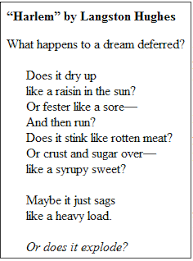

In Lorraine Hansberry’s play, A Raisin in the Sun, she immerses her audience in the story of the Younger family and how race, class, and gender affect their everyday lives. Published in 1959, the play is set in the 50s as its noted that it takes place between World War II and the present. The 50s are a time associated with white picket fences and perfect nuclear families; the American dream of a perfect life. This is in stark contrast to the lives that the Younger family is living; five people in a two-bedroom apartment, struggling to make meets’ end. It is also in contrast with the activism that rocked the nation in the 60s and 70s, leading to massive changes in legislation and social thought. The play comments on many of these issues that are tackled in the 60s and 70s, making it ahead of its time, in a sense. While the play may be best known for its depiction of a family struggling against the oppression that segregation and class lines create, it is Hansberry’s commentary on gender within the character Beneatha that was incredibly forward-thinking for the time.

Second-wave feminism was one of the many streams of activism that flowed through the country in the 60s. In spite of this movement not becoming widespread until after the play was published and performed for the first time, Beneatha subscribes to many of the ideas that feminists would be lobbying for in the next decade. In A Raisin in the Sun, Beneatha represents a modern woman. First and foremost, she is pursuing an education to become a doctor. This is an unorthodox career path for any women at the time, as highlighted by her brother, Walter Lee, stating “Ain’t many girls who decide [to be a doctor],” (I, i, 36). The fact that Beneatha is able to finish Walter’s sentence shows that this is a conversation they have had before and one that she is exasperated by. As their argument escalates, Walter asks why she couldn’t “go be a nurse like other women — or just get married and be quiet…” (I, i, 38). She clearly has been expecting a remark like this for some time, as she says it took Walter three years to say it. This illustrates how Beneatha knows what is expected of her as a woman but refutes it. This falls in line with feminist encouragement of women joining fields that aren’t considered “feminine” and would make them a primary breadwinner of their family.

In addition to her divergent career path, Beneatha also has some interesting views about marriage for the time. In spite of being courted by a wealthy George Murchison, she doesn’t have too much interest in him. She criticizes him for being shallow and tells her mother and sister-in-law that they shouldn’t hold their breath in thinking she will marry him. Often times, women would be expected by their families to marry up, in hopes of elevating their social status and/or bettering their economic situation. Beneatha says, she is “not worried about who [she is] going to marry yet — if [she] ever get[s] married,” (I, i, 50). This comment is met by incredulity from the other women, and she calms them down but saying she “probably will.” The reaction she received shows how controversial her thoughts about marriage are. Women are expected to aspire to marriage (while men are not), and any deviation from that is considered odd. This, once again, matches up to feminist rhetoric of the next two decades. Feminists would soon take up the idea that women need not place their value in when they get married or to whom they get married to.

In Act I scene ii, we’re introduced to Beneatha’s friend and apparent former flame, Asagai. He calls her “Alaiyo”, a nickname in Yoruba that initially puzzles Beneatha and Mama. She prompts him to explain the meaning of the nickname, and he answers with “One for Whom Bread — Food — Is not Enough,” (I, ii, 65). Without already having insight into Beneatha’s character, it may just seem like a way to tease her for having a big appetite. And in a sense, it is. But Hansberry’s intentions in including this nickname and exchange are less of a surface-level joke than a poignant commentary on Beneatha. She is hungry, not for food or bread, but for success. She is highly ambitious, as seen by her career choice and the many hobbies she has picked up over the years, such as playing the guitar. This drive makes her the modern woman of the play; a woman who wants to be more than a home-maker that is quiet and demure. Beneatha recognizes that those were Asagai’s intentions in calling her that, as it’s noted she understands as she replies, “Thank you,” (I, ii, 65). Beneatha appreciates this recognition of her tenacity and would likely be inclined to use the conversation as fuel to encourage her further growth.

Discussion Questions:

- How does Beneatha subvert the expectations of a woman from the 50s? How does she compare to her mother and sister-in-law in meeting or failing to meet these expectations? How do Mama and Ruth compare to Beneatha in demeanor and actions?

- How do gender roles affect the interactions between A Raisin in the Sun characters? With Beneatha and other characters, in particular? What other examples are there of gender roles being subverted?